Training the Trainer: A Mentoring Model to Increase Participation in Graduate and Postdoctoral Programs and the Workforce

Best practices that have emerged from studies over the past few decades have led to important approaches in preparing undergraduate, graduate, and postdoctoral students for success in the science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) workforce. However, fewer studies have addressed student retention, successful degree completion, and preparation for careers or retention and success for graduates once placed in those careers. Although students are placed in appropriate positions, the culture of the employer and workplace is often not sufficiently supportive to affect the retention and success of the new employee. Therefore, this initiative aims to address these gaps: both in academic training and placement at the employment site. Thus, we propose a dual train-the-trainer mentoring model where: a) the educational institution and workplace work together to build a bridge from program to placement, and b) the student is trained to use the toolkit from this program to achieve success in their careers. This model will identify best practices for mentoring, engaging, retaining, and fostering student success to weave a rich tapestry workforce and promote excellence in effecting systemic change.

We started this process with an alliance including a selected set of Minority Serving Institutions (New Mexico State University, the University of Texas at San Antonio, Tuskegee University, and Fort Valley State University) and one federal agency (U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service, USFWS) to implement the model, identifying effective and ineffective aspects, and modifying the model as needed. While this is currently an agency-specific document, it is meant to be broadly applicable and adapted (and adaptable) as we scale up to include additional educational institutions and employers. We provide the basic framework to address issues we and others before us have thus far identified. We emphasize that this is a living document, meant to be built upon as we learn and continuously improve upon best practices and discard those ineffective in the local environment.

Project Background

Broadening participation in STEM educational programs and the STEM workforce, which aligns with U.S. demographics, remains challenging, particularly in conservation and natural resource disciplines. The Alfred P. Sloan Foundation funded a group of Minority Serving Institutions (MSIs) to survey the STEM participation landscape and, through a series of listening and learning workshop sessions, to produce guidance for best practices with regard to STEM programs and workplaces. This Alliance sought to build upon existing knowledge to change institutional culture by identifying, acknowledging, and overcoming these biases, opening the pathway to graduate education and the conservation workforce for underrepresented minorities. We sought to measure our impact and disseminate lessons learned to other STEM disciplines. Our project focuses on building networks of faculty from our partner MSIs and USFWS scientists. Our approach is two-fold, starting with identifying mentoring skills through a series of workshops.

Representatives from all alliance members met, including current and former students, faculty, employers, and employees (several in multiple roles). We evaluated what we know (i.e., best practices in our respective institutions and agencies, including relevant literature) about developing science identity among underrepresented students, including feedback from students. Faculty and employer participants have all taught, mentored, and conducted research with URM STEM students. From this workshop, we developed an agenda and selected experts to correct what we, as faculty and employers, don’t know about building science identity and facilitating student and later employee success.

We invited a panel of undergraduate and graduate students from New Mexico State University, the University of Texas at San Antonio, and Tuskegee University to tell us what we don’t know as employers and faculty. We also invited two experts in STEM education at MSIs to share with us the current state and what approaches have worked in practice.

As a pilot, we matched students with mentors for summer research experiences. We followed students participating in various internship and fellowship programs, including partnerships with the US Fish and Wildlife Services, US Forest Service, US Department of Agriculture, Student Conservation Association, and the Chicago Field Museum. We assess the students' and mentors' experiences and attitudes with formative and summative evaluations. Data was collected from students before (survey), during (collected writing and communication deliverables), and after (focus groups) participation to determine satisfaction, skill acquisition, science identity, and sense of belonging.

A key feature of the summer experience was a network of mentoring support that included paired peer-to-peer mentoring, as well as designated faculty and professional mentoring personnel. Findings from the data collected emphasized the value of this networked approach to support as students were able to receive targeted support for different areas of disciplinary expertise, communications, and community engagement, while students also provided one another with invaluable self-reflection and confidence building. Students described their ability to work across professional contexts and with different professional and social contexts as being central to their ability to refine disciplinary expertise and helped them feel that they belonged and had valuable contributions to make to science.

We planned future strategies for building science identity. We identified existing best practices for mentoring and development of mentor-mentee compacts (e.g., Compact Between Biomedical Graduate Students and Their Research Advisors | AAMC). We identified existing programs aimed at improving mentoring expertise and experiences. For example, Georgia State University’s (GSU) Mentoring Enrichment Project (M-RICH, https://casa.gsu.edu/marc-the-mentoring-project/) includes a customizable mentoring handbook. We modified GSU modules/worksheets 1.1 and 4.1 to address UTSA graduate students’ specific needs with regard to belongingness, cultural mismatch, and so forth, using feedback from the surveys described above (see UTSA compact example in Appendix A). We have provided resources for mentors below to understand the importance of family support for mentees’ success. In addition, we identified approaches to connect students’ social networks to the UTSA community. Specifically, The Graduate School worked with students to develop events designed for graduate students’ friends and families. Events were piloted during Spring 2024, including during the Research Symposium that was part of Graduate Student Appreciation Week. We plan to refine these events to attract more members of students’ social networks and increase students’ sense of belongingness.

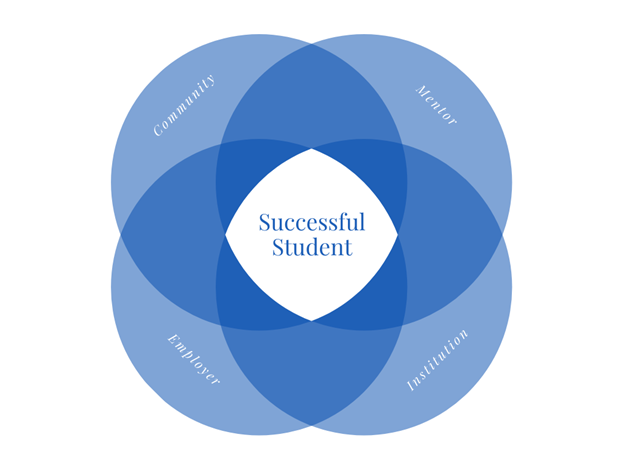

This report synthesizes recommendations and best practices from our review, conversations, and listening and learning sessions with stakeholders (students, post-docs, university personnel involved in training, and prospective employers). Through this process, we have learned from the stakeholders involved that there are often overlapping as well as individual needs of students, faculty, institutions, and employers. There is commonality in the understanding that mentoring and increasing participation of students from across all cross-sections of society can only be built upon a strong foundation of respect and deep collaboration among all stakeholders. It is essential to build empathy for all students in order to enable trust. In order to establish that trust, academic institutions, trainers, and employers alike must understand the unique needs of the current generation of students, including the barriers to their success and pathways to increase access for all students. Students facing the daunting challenges of higher education require a sense of building, a sense of community in which they can feel nurtured and in which they are mentored in the best way possible to build science identity and identity as future independent researchers, especially as they learn to mitigate experiencing the only too common effects of the imposter syndrome. Best practices must be established to address these issues to ensure the recruitment, retention, full participation, and success of all our students. Below, we present recommendations and best practices designed to address this goal for each of our triad of stakeholder groups (faculty mentors, institutions, employers) in the context of students’ communities. We include the literature informing our recommendations in appendices in order to ensure that the student contribution is recognized, understood and valued and explicitly communicated to all involved.

Recommendations

- Hold regular meetings with mentees early in their training to increase retention and understand mentees’ goals in training and placement. Individual Development Plans (IDPs) should be created early in the first year and revisited annually. Mentor-mentee compacts and mentor-mentee networking will also benefit graduate students and faculty advisors. The resource list here includes best practices from UTSA and several peer and aspirant institutions, including guides for meetings to set shared expectations (see pp. 24-32 in the Rackham Graduate School Guide for Faculty)

- Promote mental health and well being of their mentees and be aware of resources to which students can be directed as needed. Stay informed about how to access these resources and be proactive about encouraging mentees to use them when needed.

- Be prepared to mentor trainees in both formal and informal ways for multiple career paths. Faculty should take advantage of institutionally provided mentoring training, such as micro-credentials and encourage their mentees to seek such opportunities as well. Resources for mentors and mentees listed below include CIRTL, NCFDD, CIMER-NRMN, and Nature MasterClass.

- Develop an awareness of positionality and power differentials between mentors and mentees and how this affects the development of an independent researcher, and approaches to addressing these issues. Resources listed below include episodes in the National Academies' podcast series and information on multiple mentoring models (login using UTSA credentials to watch the webinar).

- Seek feedback from alumni working in non-academic careers to identify what knowledge, skills, and abilities developed in training have best served them in their positions and areas in which they wish they had received more training.

- Provide incentives and recognition for faculty engaging in training focused on effective mentorship and providing professional development (PD) for students and/or encouraging their students’ participation in PD activities.

- Institution-wide programming should be implemented to create an environment that facilitates early professional relationship-building with potential trainees and networking opportunities for students and trainers.

- Provide professional development opportunities for students to facilitate interdisciplinary networking and peer mentor relationships with graduate students in varying stages of their academic program.

- Train employees to mentor, including setting expectations.

- Partner with educational institutions to share best practices and desired professional skills.

- Provide support and resources for interns and intern supervisors such as:

- Paid internships

- Pairing interns with seasoned employees who can provide guidance and support

- Having inexperienced intern supervisors shadow experienced supervisors

- Pairing interns to reduce their anxiety

- Evaluate and Iterate

- Promote Accountability and Recognition

- Foster collaboration and knowledge-sharing

- Ensure sustainability and scalability

- Create space for students’ contributions—students have a story about why they are here, who/where their communities are—and be intentional in implementing recommendations when feasible.

- Teach/show students how to

- Ask for help

- Ask for resources

- Make a and b part of the accepted culture, potentially through peer mentoring

- Include families. Share the importance and value of postgraduate training and multiple career paths in science to the broader society, emphasize the importance of providing support for the decision to pursue a degree

- Empower students through active learning in laboratory/field settings.

Resources

|

Brainsteering grant writing program |

|

|

Developing a culture of mentorship |

https://nap.nationalacademies.org/resource/25568/interactive/tools-and-resources.html#section1 |

|

Georgia State University M-RICH program |

|

|

iBiology mentor program |

|

|

Keep Running With Us program at UTSA |

https://future.utsa.edu/graduate/krwu/ View article: https://bit.ly/KRWU |

|

NRMN STEM Mentor programs |

|

|

Training for scientists interested in careers outside of academia |

|

|

The Science of Effective Mentoring in STEMM - Podcasts |

https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/the-science-of-effective-mentoring-in-stemm |

|

CITI Training: Mental Health and Mentoring Graduate Students |

https://about.citiprogram.org/blog/mental-health-and-mentoring-graduate-students/ |

|

Council of Graduate Schools (CGS) Mentoring Resources |

https://cgsnet.org/data-insights/graduate-professional-development/mentoring-resources |

|

NCFDD Mentor Map |

|

|

Rackham Graduate School Guide for Faculty |

|

| UTSA Mentoring Hub |